Math anxiety, also referred to as math phobia, describes the worry or fear of failure associated with math achievement and is directly linked to poor math performance.

Most often, people who experience math anxiety believe that they are bad at math and because of this have constructed a mindset that expects failure. They tend to have poor or underdeveloped math skills and struggle with effort-based decision-making in the real world. Research also demonstrates the negative impact of math anxiety on working memory capacity and functioning.

When faced with a mathematical problem, people with math anxiety might feel helpless. They may begin to panic and struggle with a rise in mental disorganization. Often in these situations little in the way of intervention and support is available, so as the math anxiety perpetuates, the idea of giving up or putting in less effort becomes much more appealing than facing the problem at hand.

Math Phobia From an Early Age

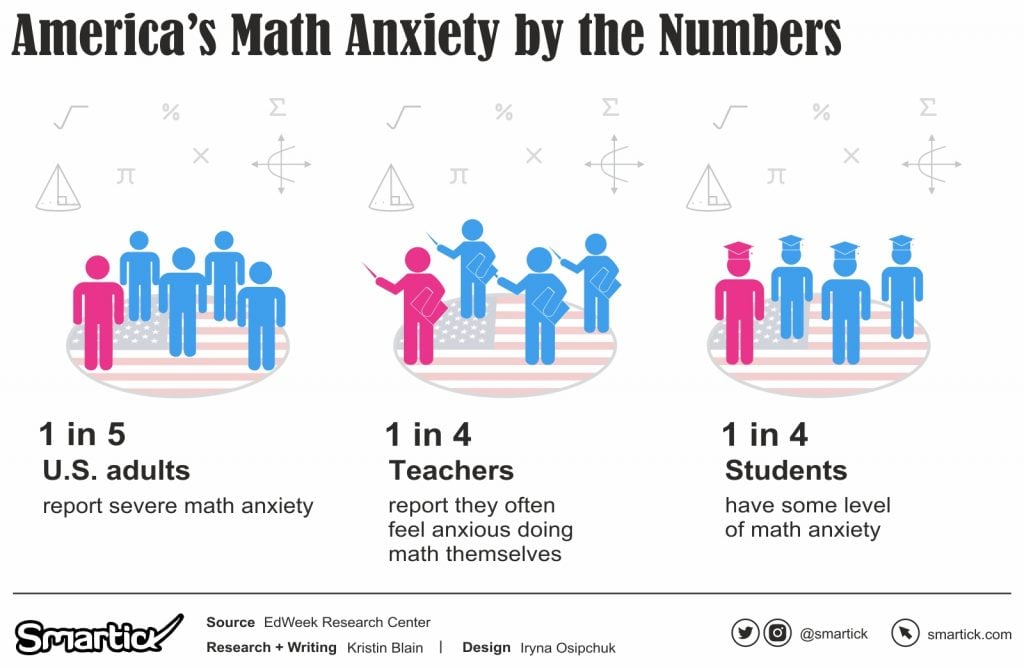

For far too many children in the United States, math phobia can begin as early as the first year of school. According to EdWeek Research Center, 1 in 4 students have some level of math anxiety.

For many of these students, math anxiety translates to fear of test-taking. In this case, students who perform well on non-graded math assignments are unable to showcase their abilities when they know a value will be allocated to those abilities compared with others.

For other students, math anxiety stems from the inability to grasp math concepts or to apply critical thinking skills such as reasoning and analysis. Unfortunately, children who struggle with grasping math concepts and thinking at an early age find themselves on a downward spiral as concepts in later years become more abstract, require multiple steps for solving, and are overall more cognitively-demanding.

Teaching With Math Anxiety

In order to effectively teach math, educators need to first feel confident with the mathematical concepts and reasoning for themselves. However, 1 in 4 teachers in the U.S. report feeling anxious doing math. This anxiety can manifest during planning, instruction, and evaluation of student ability.

Teachers with math anxiety may enforce the use of the strategy that they feel most comfortable with when solving a problem—even if that strategy is not the only way to the answer. This insecurity in instruction generates narrow pathways to success for only a handful of students that understand the teacher’s method. The rest of the class—those who might be more successful using a strategy unfamiliar to the teacher—will be left behind.

While other classroom subjects like reading and writing tend to have joyful and creative connotations, math is often taught as a set of procedures and calculations to one right solution. Timed tests, speed pressure, and getting to the right answer first work contrary to what brain research tells us—that visual representations of ideas are integral to strengthening brain connections in mathematical growth. Using this kind of researched-based pedagogy can help teachers to widen the pathway to success by approaching math as a subject of depth, trial-and-error, and new ideas.

Developing subject knowledge is key to teaching success. Teachers facing math anxiety should undergo professional development that offers new ways to think about math concepts and methods. They can collaborate with mentor teachers who have more expertise in explicitly teaching math. They can also work on changing their own mindsets by using positive language and creative activities to make math learning fun for their students—and for themselves!

Math Anxiety Beyond the Classroom

Fear of math isn’t restricted to school age students and their classroom teachers. It reaches beyond the classroom to where the need for math confidence can be a deciding factor in financial security, job success, and overall health.

Today, 1 in 5 adults in the United States struggle with severe math anxiety, while 93% of adults report having at least some apprehension about the subject.

Math anxiety negatively affects reflective thinking and effort-based decision-making in the real world. It can result in poor financial planning, misinterpretations of personal health charts, and the underperformance of math-related tasks at work—perhaps most distressingly in the field of healthcare, where the miscalculation of medicinal dosages can have a serious impact on the lives of others.

Children with math anxiety tend to grow up to be parents with math anxiety, and the way they approach math as adults—as well the language they use in front of their children—serves as a model of math avoidance, stress, and low self-esteem for the next generation.

Is Your Child Struggling With Math Anxiety?

There is a difference between “just not liking” math and math anxiety. Here are some signs that indicate your child may really be struggling:

- Physical stress such as chest pain, headaches, or tightness in the shoulders, jaw, neck, arms, or back

- Tiredness and irritability

- Disruptive behavior or lack of attention during math class

- Incomplete work, or avoidance of math assignments altogether

- Math work completed correctly, but poor scores on math tests.

Building Immunity to Math Anxiety

Research has shown that a fear of math can be contagious. Students whose parents and teachers exemplify negative attitudes about math are more likely to learn less math and become nervous about math themselves.

That’s why it’s important for parents and teachers to begin building immunity to math anxiety early on. Practical math applications are all around us and shouldn’t be avoided. Children should be encouraged to try out their math skills in the real world, and to play math games to make the learning fun. When adults repair their own attitudes towards math, using errors as opportunities for growth and celebrating the superpowers that come with problem-solving, the subject loses its stigma, and a new generation of math-confident kids begins.